We are now to the point where we need to discuss what our body does in response to pain and how opioids (external opioids like morphine) interact with our body process.

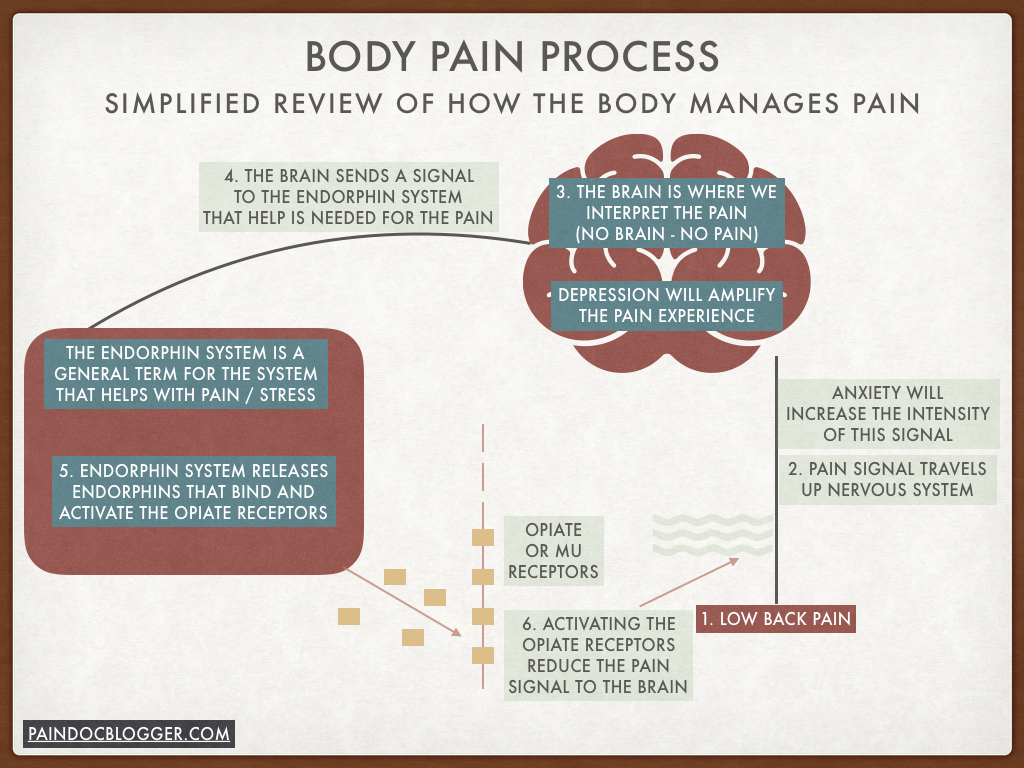

We will start first by reviewing a basic illustration that describes how the body naturally manages our pain experience. Look at the illustration first and then I will walk through the process.

In this example the person experiences back pain (1), that signal travels up the nervous system to the brain. Anxiety aggravates our nervous system, so the more anxious you are, the more pain you are going to experience. Think of stress as both physical and emotional. This is why medical providers are constantly worried about stress and its overall impact on your health, pain and emotional experience. Medications that manage stress or influence the nervous system (think gabapentin (Neurontin); pregabalin (Lyrica)) can calm the nervous system and help reduce your pain experience. They do other things but this is one potential benefit.

Now back to the brain in step (3). The brain interprets or PERCEIVES the pain. All pain has to be perceived by the brain at some level. In some way we have to ATTEND to that pain. This is why when we are distracted by something else (e.g., good book, movie, sewing, a game, other people, etc.) our pain will go into the background somewhat. An additional point is that DEPRESSION will amplify our perception of pain. This is why providers are focused on your mood as part of their pain assessment. More depression, more pain.

In step (4) the brain says “Hey, I need some help here with this pain” and sends a signal to the ENDORPHIN SYSTEM to provide that help. IMPORTANT NOTE: This is a simplified presentation of the body and I am using general terms. The body is very complicated and this is where medical providers struggle to be able to educate patients. They will get deep in the weeds with patients, throwing out terms like the “dorsal horn” and “mu receptors” that will lead us down to a place where nothing will make sense in the 10 minute visit. Here we are using the overarching mechanisms involved to present an overview.

Most of us understand the basics of the ENDORPHIN SYSTEM. It is our internal pain and stress management system. It is the thing most people relate to the “runner’s high” that we get when we exercise or how our body responds to an injury or a threat. It has many different purposes and functions in this general sense. In this specific situation it is responsible for releasing ENDORPHINS (5) that are these OPIATE-LIKE internal substances that will BIND to the mu receptors (our internal opiate receptors) and then ACTIVATE those receptors (6). Activating the receptors will lead to a DISRUPTION OF THE PAIN TRAVELING TO THE BRAIN.

That is a summary of how our internal system works and influences our pain experience. Not that complicated, right? Actually, it is really complicated and, again, that is where some struggle to explain this in an understandable way.

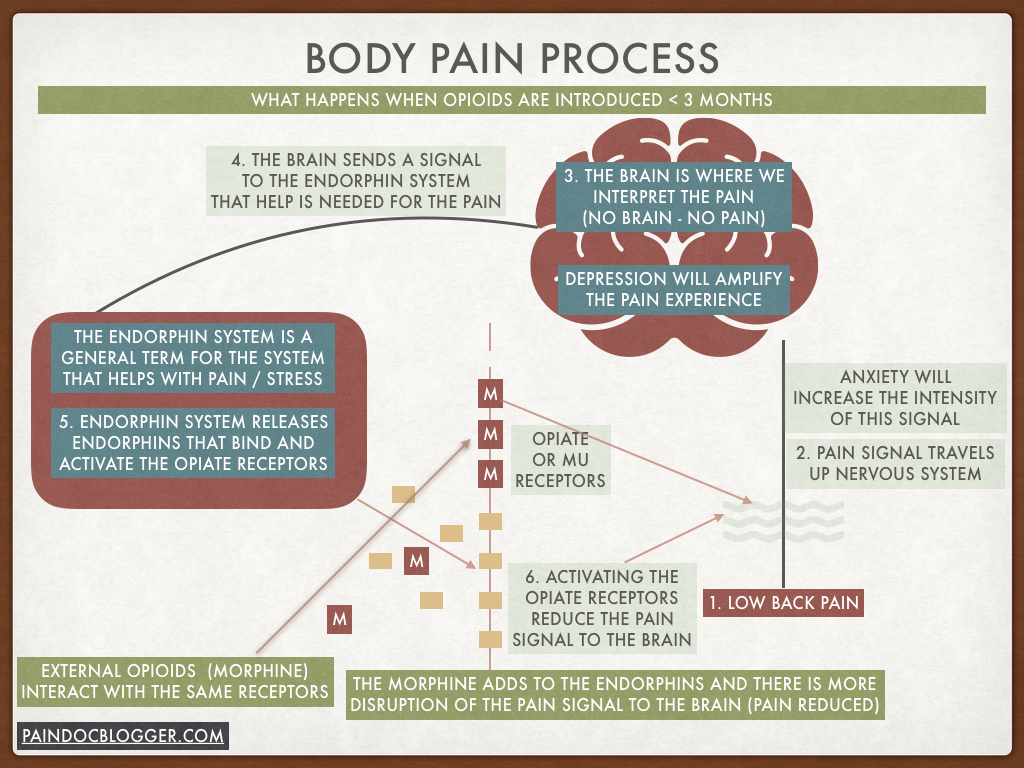

Now here’s what happens when we ADD an EXTERNAL OPIOID-LIKE SUBSTANCE to this system. In the illustration, we start first with how opioids work on a person when they are only using them for the FIRST 3 MONTHS, so short-term use.

In this example, the MORPHINE ADDS TO WHAT THE BODY WAS ALREADY DOING WITH THE ENDORPHINS. This leads to further disruption of the pain signal from the low back to the brain, producing MORE PAIN RELIEF. It is easy to understand why there is reasonable data that suggests external opioids used for a short-period of time can lead to pain relief. The literature supports this use at a limited level due to other potential problems such as exposure that could lead to an Opioid Use Disorder. That being said, we do acknowledge in this blog that there may be a role for opioids with acute pain conditions.

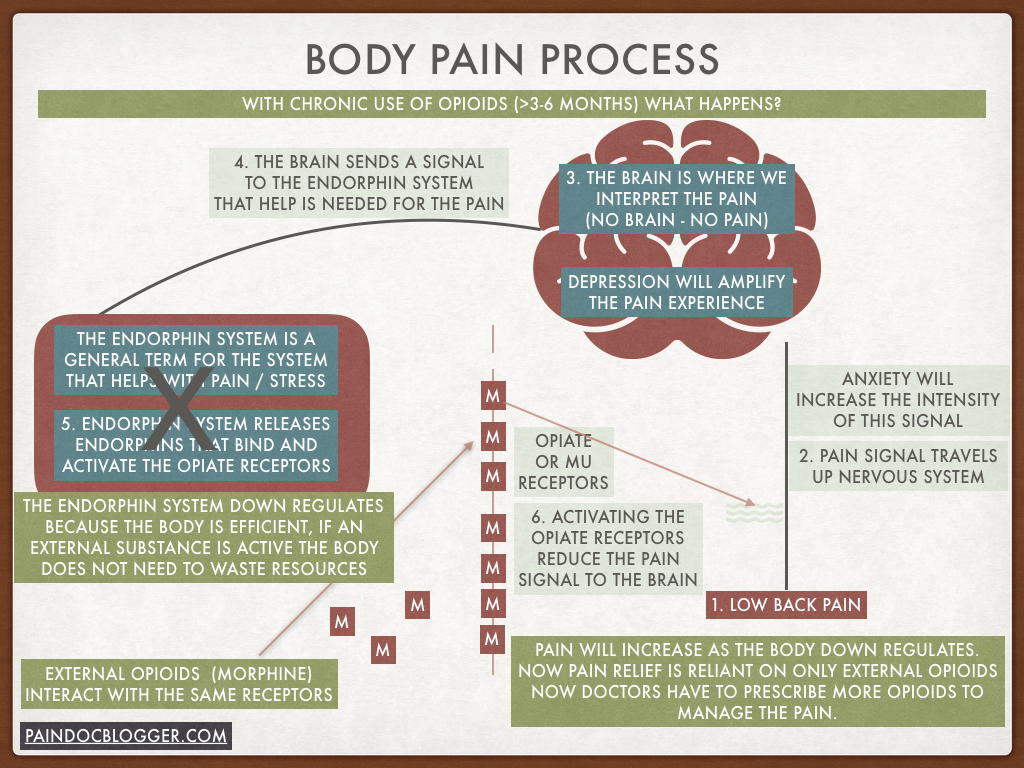

Now we start to review the process of what happens when an external opioid is continued for more than 3 months or chronically within the body. This relates directly to the CDC guidelines where they indicate that “chronic opioids for chronic non-cancer pain are CONTRAINDICATED.”

In this scenario, we start to see how our bodies are creative and adaptive, as well as efficient. As the MORPHINE continues to bombard the body over the first 3-6 months, our body will begin to DOWN REGULATE the endorphin system until that system is no longer actively involved in your pain control. You begin to feel more pain due to the open receptors and you discuss this with your provider. You and they decide that an INCREASE IN YOUR PAIN MEDICATION is indicated to make up for the fact that your body is no longer helping with your pain control. This works for the short-term, but this is just the first in many increases you will need if we do not stay on the top of the process.

One of the problems that occurs is that you become acutely aware of the medication flowing in and out of your body because the body is no longer providing backup to the medication. As your receptors become desensitized to the opioids, they develop tolerance and do not work as well. This causes an additional problem where we again experience more pain, so the provider increases the pain medication. Now our body is MORE DEPENDENT on the medication. Usually around this time, we are switching to A LONG ACTING medication because the patient is noticing the short-acting medication (hydrocodone / Vicodin or oxycodone / Percocet) are now only lasting 3-4 hours, not the 6-8 hours they did initially. Remember, the body is now being BOMBARDED BY AN OUTSIDE SUBSTANCE. Do you like getting PELTED BY FREEZING RAIN? Do you think your body enjoys a similar experience?

The result is this ever increasing reliance on the opioid to impact the pain: the ever reducing involvement of the body, and the ever increasing amount of opioid being prescribed due to the combination of reduced body involvement and receptor tolerance. Along the way, your body will start to ADD MORE RECEPTORS to attempt to adapt to the situation, but the same process will occur with those receptors and we will need to ADD MORE medication to get the same perceived pain relief. Well – this sucks!

Now at this point, the person on pain medication will say “but it works for me! I still feel it working!” But is it really working? The duration of the medications action becomes less and less. The person now only has a few good hours of the day and the rest are spent waiting for the next dose. The opioids at these higher doses are now impacting our SLEEP, our daytime energy, our cognition / concentration, our personality and are likely leading to DEPRESSION. We are getting more drugged and depressed.

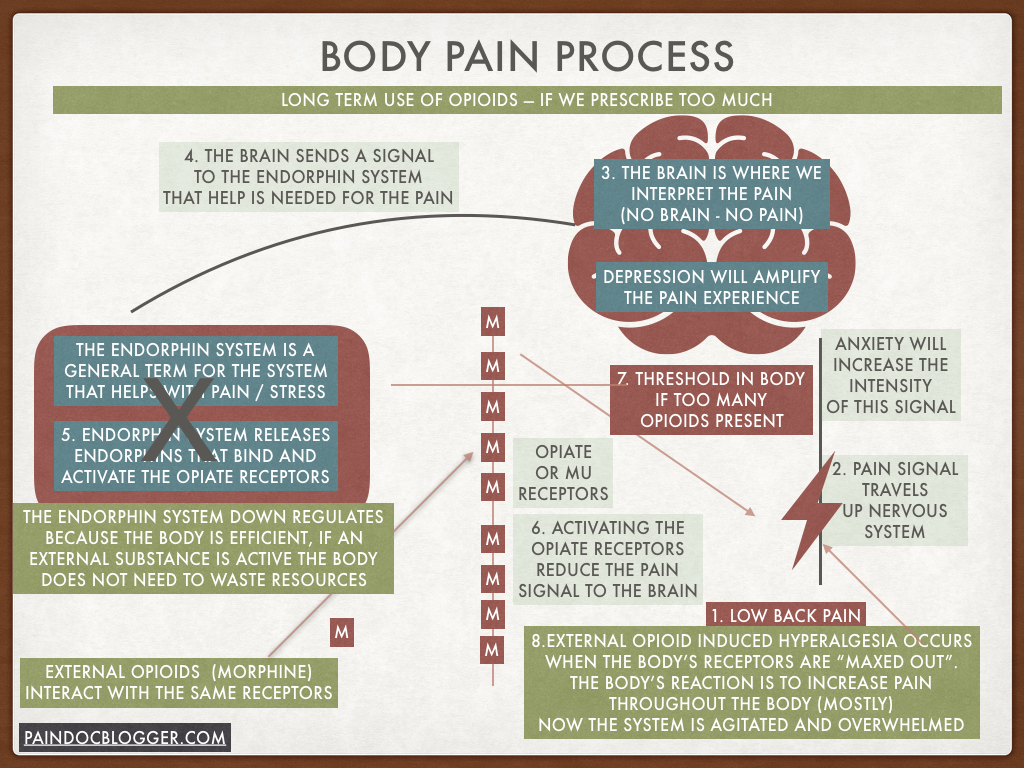

On to the final diagram of what happens when we actually get too much of the external opioids in our system.

In the past we inaccurately thought that the body could handle an unlimited supply of opioids, meaning that if we continued to increase the dose, the body would adjust to the higher amount and allow the person to continue to tolerate the increased and higher doses. The thought was that our body would just continue to benefit from the higher doses and continue to gain pain relief. How wrong we all were.

What we now know is that our body has thresholds and we eventually will go beyond what it can tolerate. One part of that is the increased risk of overdose due to the higher dose. We reviewed this in an earlier post. The other part is that our body actually starts to fight back against the higher dose by actually PRODUCING PAIN when we go beyond what our body can tolerate. This phenomenon is call OPIOID INDUCED HYPERALGESIA. ALGESIA is pain, so this is a hyper or increased pain condition that is directly due to the pain medications that we are using to reduce pain.

We all should understand that our body has limits. How could we all be so off on this one? An example would be an overactive thyroid, which is our body producing too much thyroid hormone. Even though it is our own body doing this to itself, we do not feel well. This is why we end of ablating part of the thyroid to reduce the amount that our body is producing.

So, it is not hard to imagine that an outside substance that goes beyond what our body can tolerate would eventually stop producing continued pain relief. What happens is this condition of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. This can lead to two separate types of pain experiences:

- Most common is an increased pain throughout the body that produces pain that looks most similar to the condition of fibromyalgia. In this situation, the body hurts, the person has tenderness throughout the body, they develop poor sleep patterns, they are fatigued, their muscles hurt and their main source of pain also gets worse. REMEMBER this situation because I will post in the future about fibromyalgia and we will begin to see some similarities.

- The less common type is just focused increase in pain and tenderness at the place where they normally have pain (e.g., low back in this example).

Historically, we would treat this by increasing the dose of opioids. This would work for a while, the person would feel better and then the new threshold would come down like a hammer and the hyperalgesia would be back. We would continue this dance until the person was on massive doses of 1,000-2,000 morphine milligrams equivalent. And, thus, this is how you get into an opioid crisis.

The correct treatment is to gradually and persistently wean the patient off the opioids in a caring, slow, gentle and humane way. As they get below their individual hyperalgesia threshold, their pain will begin to improve – SIGNIFICANTLY. Imagine if the medication you were being prescribed to help your pain was actually making your pain worse!

We used to think that opioid-induced hyperalgesia happened at massive doses, 700 mg of morphine or even over 1,000 mg of morphine. Now we realize it can happen at any dose but is very likely at doses greater than 100 mg of morphine and, in my opinion, guaranteed at doses over 200 mg of morphine.

Now we have reviewed 3 of the 4 reasons why the way we use opioids for chronic non-cancer pain HAD TO CHANGE FUNDAMENTALLY. I apologize for the length of these posts but this detail is required to fully explain what happens in our bodies and then understand a different path to treat those with chronic non-cancer pain.

As always, the opinions expressed here are mine and mine alone, meaning they are not necessarily those of Marshfield Clinic Health System.